A C Programmer Learns Javascript: Making RasterCarve

4 Jan 2020

TL;DR I kept building RasterCarve, culminating with a full-fledged web interface.

My most recent side project, RasterCarve, is a package to produce CNC toolpaths for engraving images. The title is perhaps a bit misleading – the different parts of RasterCarve ended up being written in a whole array of languages: the core is in Python (the subject of my previous post), an associated preview utility is in C++, and the web interface – the fanciest of the bunch – is in the usual hodgepodge of Javascript/HTML/CSS (and of course some hacked-togther shell scripts to glue everything together).

This post is in one sense a follow-on to my last one in that I’ll detail the continued development of RasterCarve. But along the way, I also want to show how building software is a uniquely incremental process – unique, perhaps, among the engineering disciplines. Keep this in mind as you read along.

Part 1: argparse is a Miracle

I’ll pick up where my last post left off. RasterCarve existed as a hacky Python script, with all parameters configured by hand-editing the Python file (convenient, I know).

It looked something like this:

import cv2

import math

import numpy as np

import sys

#### Machine configuration

FEED_RATE = 80 # in / min

PLUNGE_RATE = 30 # in / min

RAPID_RATE = 180 # in / min (used only for time estimation)

SAFE_Z = .1 # tool will start/end this high from material

TRAVERSE_Z = 2 # ending height (in)

MAX_DEPTH = .080 # full black is this many inches deep

TOOL_ANGLE = 30 # included angle of tool (we assume a V-bit). change if needed

#### Image size

DESIRED_WIDTH = 4 # desired width in inches (change this to scale image)

#### Cutting Parameters

LINE_SPACING_FACTOR = 1.0 # Vectric recommends 10-20% for wood

LINE_ANGLE = 22.5 # angle of lines across image, [0-90) degrees

LINEAR_RESOLUTION = .01 # spacing between image samples along a line (inches)This system worked well enough for me (probably because I’m the one

who wrote it), but for practical use it was untenable. So I investigated

command-line parsing in Python and found argparse,

which has since earned the spot of my favorite API of all time. Why?

With just a couple lines of code, I went from no command-line interface

at all to a fully customized one with built-in error handling and

automatic help text generation.

On that last point, just see for yourself:

dim_group = parser.add_argument_group('output dimensions', 'Exactly one required.')

mutex_group = dim_group.add_mutually_exclusive_group(required=True)

mutex_group.add_argument('--width', help='output width (in)', action='store', dest='width', type=float, default=argparse.SUPPRESS)

mutex_group.add_argument('--height', help='output height (in)', action='store', dest='height', type=float, default=argparse.SUPPRESS)

mach_group = parser.add_argument_group('machine configuration')

mach_group.add_argument('-f', help='engraving feed rate (in/min)', action='store', dest='feed_rate', default=DEF_FEED_RATE, type=float)

mach_group.add_argument('-p', help='engraving plunge rate (in/min)', action='store', dest='plunge_rate', default=DEF_PLUNGE_RATE, type=float)

mach_group.add_argument('--rapid', help='rapid traverse rate (for time estimation only)', action='store', dest='rapid_rate', default=DEF_RAPID_RATE, type=float)

mach_group.add_argument('-z', help='rapid traverse height (in)', action='store', dest='safe_z', default=DEF_SAFE_Z, type=float)

mach_group.add_argument('--end-z', help='Z height of final traverse (in)', action='store', dest='traverse_z', default=DEF_TRAVERSE_Z, type=float)

mach_group.add_argument('-t', help='included angle of tool (deg)', action='store', dest='tool_angle', default=DEF_TOOL_ANGLE, type=float)

cut_group = parser.add_argument_group('engraving parameters')

cut_group.add_argument('-d', help='maximum engraving depth (in)', action='store', dest='max_depth', default=DEF_MAX_DEPTH, type=float)

cut_group.add_argument('-a', help='angle of grooves from horizontal (deg)', action='store', dest='line_angle', default=DEF_LINE_ANGLE, type=float)

cut_group.add_argument('-s', help='stepover percentage (affects spacing between lines)', action='store', dest='stepover', default=DEF_STEPOVER, type=float)

cut_group.add_argument('-r', help='distance between successive G-code points (in)', action='store', dest='linear_resolution', default=DEF_LINEAR_RESOLUTION, type=float)

cut_group.add_argument('--dots', help='engrave using dots instead of lines (experimental)', action='store_true', dest='pointmode', default=argparse.SUPPRESS)

gcode_group = parser.add_argument_group('G-code parameters')

gcode_group.add_argument('--no-line-numbers', help='suppress G-code line numbers (dangerous on ShopBot!)', action='store_true', dest='suppress_linenos', default=argparse.SUPPRESS)

parser.add_argument('--debug', help='print debug messages', action='store_true', dest='debug', default=argparse.SUPPRESS)

parser.add_argument('-q', help='disable progress and statistics', action='store_true', dest='quiet', default=argparse.SUPPRESS)

parser.add_argument('--version', help="show program's version number and exit", action='version', version=__version__)With these parameters, the library automatically produces a beautiful help screen, like so:

usage: rastercarve [-h] (--width WIDTH | --height HEIGHT) [-f FEED_RATE]

[-p PLUNGE_RATE] [--rapid RAPID_RATE] [-z SAFE_Z]

[--end-z TRAVERSE_Z] [-t TOOL_ANGLE] [-d MAX_DEPTH]

[-a LINE_ANGLE] [-s STEPOVER] [-r LINEAR_RESOLUTION]

[--dots] [--no-line-numbers] [--debug] [-q] [--version]

filename

Generate G-code to engrave raster images.

positional arguments:

filename input image (any OpenCV-supported format)

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--debug print debug messages

-q disable progress and statistics

--version show program's version number and exit

output dimensions:

Exactly one required.

--width WIDTH output width (in)

--height HEIGHT output height (in)

machine configuration:

-f FEED_RATE engraving feed rate (in/min) (default: 100)

-p PLUNGE_RATE engraving plunge rate (in/min) (default: 30)

--rapid RAPID_RATE rapid traverse rate (for time estimation only)

(default: 240)

-z SAFE_Z rapid traverse height (in) (default: 0.1)

--end-z TRAVERSE_Z Z height of final traverse (in) (default: 2)

-t TOOL_ANGLE included angle of tool (deg) (default: 30)

engraving parameters:

-d MAX_DEPTH maximum engraving depth (in) (default: 0.08)

-a LINE_ANGLE angle of grooves from horizontal (deg) (default: 22.5)

-s STEPOVER stepover percentage (affects spacing between lines)

(default: 110)

-r LINEAR_RESOLUTION distance between successive G-code points (in)

(default: 0.01)

--dots engrave using dots instead of lines (experimental)

G-code parameters:

--no-line-numbers suppress G-code line numbers (dangerous on ShopBot!)Now, this might not seem so impressive if you’re someone used to a

high-level language, but keep in mind that in something like C, a full

command line parser and help text generator like the one above would’ve

taken several hours to build from scratch, or several times the amount

of code as I used here, even with a library function like

getopt.

With the CLI built, I published RasterCarve as a PyPI package. Again, for a C programmer, PyPI is at once a miracle and a security nightmare: with it, package management is an absolute breeze, but I was mildly shocked at the lack of curation, especially with a flat namespace. Oh, well.

As an aside, I also added a nice progress bar – this was also surprisingly easy with the tqdm library. It took, quite literally, two lines of code to get started with a simple progress bar:

from tqdm import tqdm

for i in tqdm(range(10000)):

...Part 2: rastercarve-preview

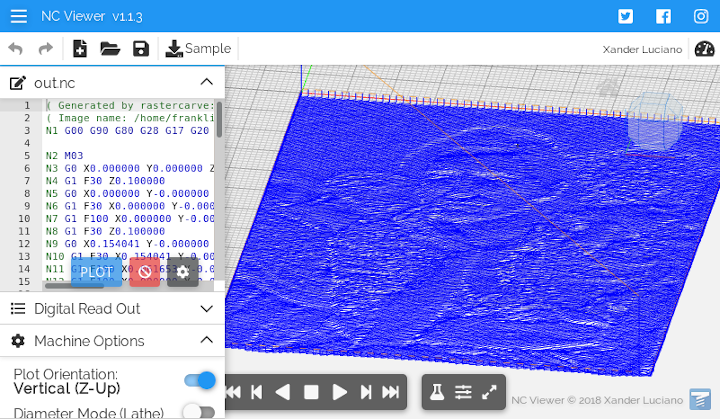

Until now, I’d been using the online NC Viewer as my previewing tool, and it served well enough. It did have one shortcoming, though – it can’t simulate the effect of a toolpath on a piece of material. I was able to work around this by panning the displayed toolpath at an angle to see some of the image’s texture (above), but this was suboptimal.

What I really wanted was a standalone utility that produced something like the ShopBot previewer shown above, but without all the bloat and dependence on Windows.

I decided on SVG as the output format of the previewer, for a couple of reasons: first, it’s a vector format, so zooming around the preview image would not compromise quality; and second, I knew that it was an XML-based format, so directly outputting to it would not require too much additional code.

As for parsing the input G-code, I used Dillon Huff’s delightful gpr G-code

parser. With it, I was able to extract from RasterCarve’s G-code output

a series of \(\mathbf{v_1, \cdots, v_n} = (x,

y, z) \in \mathbb{R}^3\) that represented the movement of the

tool (assumed to be a V-bit) through space.

By assuming the material is a flat sheet occupying all \(z < 0\), the shapes carved onto the material at each \(\mathbf{v_i}\) can be determined; for a V-bit, this engraved shape at each point is a circle of radius

\[ r = z \tan \theta, \]

where \(\theta\) is the included angle of the tool’s cutting bit.

G-code is linearly interpolated between each \(\mathbf{v_i}\), so the final engraving result is the region swept out by the tool’s cross section on the plane \(z=0\).

This raises an interesting question. Given a function \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3\) defined by \(t \mapsto (x, y, r)\), interpreted as the time-varying location and radius of a circle in a plane, how do we render the region this circle sweeps out?

We can of course use the usual mathematical trick of limits by sampling this function at many closely spaced \(t\), and drawing the circle given by \(f(t)\). And it works:

But this method is impractical – sure, it’s possible to get a reasonable-looking image – but only with an absurd amount of dots, leading to SVGs in the tens to even hundreds of megabytes. (The preview above, as sparse as the dots are, weighs close to a megabyte.) Clearly there’s room for improvement.

After this first attempt, I attempted to better describe underlying geometry of the problem. I assumed that the function was piecewise linear and continuous – that it was composed of many connected line segments. This gives the insight that the engraved result of the function is the union of convex hulls of pairs of adjacent circles. That is, for every pair of points in the G-code, the corresponding result on a piece of material is a shape like this:

The overall path, then, is the result of combining a sequence of these shapes with common endpoints.2

Though this formulation is fairly straightforward to describe mathematically, implementing it in code was more difficult than I’d imagined. So I set it aside in favor a simpler approximation.

What my current implementation of rastercarve-preview

does instead is an approximation of the path with a polygon. For each

point \(\mathbf{v_i}\) in the G-code,

the program calculates a normal vector \(\mathbf{\hat{n}}\) orthogonal to the

toolpath at that point (by simply rotating the direction of movement by

90° in either direction).3 Then, \(\mathbf{v_i} \pm r \mathbf{\hat{n}}\) are

the vertices on the polygon contributed by the G-code point \(\mathbf{v_i}\).

This gives a surprisingly good approximation, as shown above. It only fails when the toolpath has rapid changes in Z, but as long as the overall engraving depth is small, the error is minimal.

With this method, “Migrant Mother” becomes:

This result was good enough. Sure, the inner perfectionist in me is still dissatisfied, but in reality the previewer works well enough for practical purposes.

Part 3: RasterCarve Live

Now that the core functionality of RasterCarve was built, it was time

to put lipstick on a – err, build a web interface for it. I chose to go

the “hip” route with a Express/Node.js backend that wrapped RasterCarve

and its previewer, behind a frontend built with Bootstrap. My working

name for it was rastercarve-web, but I changed it to

“RasterCarve Live” to go with its domain name, rastercarve.live.

I’ve probably written more C than English in my life, so it’s shaped my preferences rather strongly. I like strong typing, for one – or at the very least, having a good way of figuring out what a variable’s type is, and finding documentation on it. I would find none that in Javascript.

I’m also used to having to fully understand the code I put out, so it came as a shock how much I could get away with by blindly copy-pasting snippets off Stack Overflow. An entire GUI was built this way, along with all the frontend and backend JS that went with it (by which I mean the entirety of RasterCarve Live). Not that it’s entirely a bad thing, though – the lessened mental workload from not having to make trivial GUI components from scratch meant I could spend more time focusing on the functionality of the product.

The most technically interesting piece of RasterCarve Live ended up being the aggressive caching system I built, largely by accident. The client-side code first computes a MD5 hash of the user’s input image and sends that hash in a request, along with the engraving parameters, in place of the actual file data.4 It works as follows:

If the server has served an earlier request (with the exact same parameters) on an image with the same hash, simply return the result of the earlier query.

If the server has served an earlier request with different parameters on an image with the same hash, perform the new query on that previous image (which is stored in a short-term cache).

If the image is not in cache, request that the client re-attempt the request with the actual image data.

This multi-tiered caching approach avoids having to re-upload the same image multiple times – the most time-consuming part of a request. It also allows the server to precache some sample images, allowing file upload to be skipped entirely. For privacy reasons (and the practical reason of not eating up my EC2 disk space), files are purged from cache 15 minutes after upload.

Conclusion: “Just Shut up and Build the Damn Thing”

When I’m thinking about taking on a side project, I often find myself trying to anticipate all the obstacles that might come up along – having next to no experience in the language I’m planning on writing it in, for example. Or how in the world I’m going to mathematically describe the region swept out by a circle of varying position and diameter in a plane. But I learned from this project that that’s just not how software is built.

I didn’t set out on this project with a step-by-step plan for how I was going to build a CAM toolpather in Python, then a previewer in C++, and then a web interface in Node.js, JQuery, and Bootstrap – I set out with an idea to build a hacky little Python script to replace a $149 commerical program I didn’t want to buy.

But after each step, I kept adding more and more – I built a previewer because I was tired of pasting my G-code into NC Viewer.5 I built a web interface because the previewer already outputted SVG, so it just seemed logical.

The point here (and the less crudely worded version of this section’s header) is that building software is an inherently incremental process – one where it’s difficult to see too far ahead. Sure, it helps to take a step back occasionally and plan out your next steps, but trying to look too far ahead can be counterproductive – and in some cases, prevent you from taking on a project entirely, for fear of difficulty far down the road. But it’s the difficult projects that are able to transform initially unfamiliar territory into well-trodden ground, and for that reason, I believe difficulty should be actively sought out – not avoided.

It is surprisingly hard to find a decent image of the convex hull of two circles – you may notice that this image is in fact not a true convex hull (the points of tangency on the two circles are not exactly tangent). But you get the idea.↩︎

This is distinct from saying that the overall result is the convex hull of all the circles along the path – that gives a very different result, since large circles can “shadow” smaller parts of the path.↩︎

The direction of movement was approximated by looking at either the next or previous engraving point. This was the source of many edge cases, but I eventually dealt with them all (I hope!).↩︎

Yes, MD5. It’s fast, automatically computed by Express, and collision resistance is not critical in this application.↩︎

This is not to say that NC Viewer is a bad program, by any means – but it just wasn’t suited for my application.↩︎